One of the most delightful discoveries in my study of Isaiah was seeing how Matthew understood Isaiah. In short, Matthew recognized that Jesus was the very one that Isaiah had spoken of. When we look at the second half of Isaiah, I ‘ll show you how that plays out there, but in this post I want you to see how Matthew presents Jesus as the figure that Isaiah develops in chapters 6-12.

It is commonly known that Matthew begins his gospel with the genealogy of Jesus. The casual reader recognizes that Jesus is the last in a long line of kings and heirs to the Davidic throne. The natural observation is that if Israel had sovereignty when Jesus was born, he would be the next king. Rather than presenting an uninterrupted line of succession, however, Matthew breaks the genealogy at two places, creating three lists of fourteen generations each. While this may well have been done for mnemonic (memory) purposes, the places where the breaks are made are important. The first break is at “David the king.” The second break is at the “deportation to Babylon.” To make sure that you don’t miss this, Matthew repeats that this is his structure in verse 17.

The focus on David is easily understood as he was the founder of the dynasty and the recipient of a promise that his line would always hold the throne (2 Sam 7:9-16). The longing for the “son of David” who would fulfill this promise is well known (and see Matt 1:20). The reason why Matthew emphasizes the exile in the genealogy may not be as obvious, especially if you don’t understand Isaiah 6-10. The prophecy of Immanuel says that not only will a child be born, but he will be raised in poverty which is the result of invasion. In chapters 7-10, Isaiah predicts the coming of Assyria. This is the beginning of Israel’s subjugation which later results in the deportation by Babylon (predicted in chapter 39). In chapters 40-48, Isaiah foresees a physical restoration from exile under Cyrus. But the exile does not end with that. Israel does not have independence from foreign rule, and the spiritual exile is surely never resolved. By breaking the genealogy at the exile, I believe that Matthew is reminding his readers both of their present exile as well as the fact that one born in that exile would deliver from that exile. I ‘ll talk more about this when we get to the Servant Songs in chapters 42-53.

That Jesus is the “Immanuel” predicted in Isaiah 7:14 is stated in no uncertain terms by Matthew. Mary was a virgin; her conception was by the Holy Spirit. The virgin would bear a son. The boy will save his people from their sins. All of this comes right out of Isaiah, and all but the last sentence comes from chapter 7. As he quotes 7:14, Matthew says, “All this took place to fulfill what the Lord had spoken by the prophet” (Matt 1:23). Jesus is Immanuel, “God with us,” the heir of the house of David, born in poverty to a people in exile. As Jesus grows up, we see that he indeed knows how to “refuse the evil and choose the good” (Isa 7:15-16).

After Jesus’s baptism and temptation, he begins his ministry. It is interesting how Matthew introduces this, and if you don’t know (or read) Isaiah, you ‘ll miss something. I ‘ll quote it here so your memory is refreshed (and perhaps you ‘ll make a typical mistake).

Matthew 4:12-16 (ESV) “Now when he heard that John had been arrested, he withdrew into Galilee. 13 And leaving Nazareth he went and lived in Capernaum by the sea, in the territory of Zebulun and Naphtali, 14 so that what was spoken by the prophet Isaiah might be fulfilled: 15 “The land of Zebulun and the land of Naphtali, the way of the sea, beyond the Jordan, Galilee of the Gentiles— 16 the people dwelling in darkness have seen a great light, and for those dwelling in the region and shadow of death, on them a light has dawned.””

On the face of it, you might think that Matthew is merely explaining why Jesus ministered in Galilee. Of course, he is doing that. But he’s doing much more. By quoting this passage, he is identifying Jesus with the light prophesied in Isaiah 9. When you keep reading in Isaiah 9, you see that this light is a child, a son, one who carries the government on his shoulder and who is called “Mighty God” and “Prince of Peace.” This individual will rule on the throne of David and over his kingdom without end. Matthew expects you to make this connection; he is not quoting out of context. Matthew is saying that the one Isaiah prophesied has arrived.

You could wish that Matthew was even more blatant. Why didn’t he go ahead and quote Isaiah 9:6-7? One reason may be that Matthew wasn’t anticipating the biblically illiterate readers of the 20th century; he expected his readers would be familiar with the Bible and would grasp this. In fact, I think that Matthew was quite kind to us. He could, legitimately I believe, expected us to know that Jesus was the fulfillment of Isaiah 9 because he already told us that Jesus was the fulfillment of Isaiah 7. And, as I have shown already, the individual prophesied in chapter 7 is the same one as in chapters 9 and 11. But just so that no one misses it, Matthew states it explicitly: Jesus is the figure of Isaiah 7; Jesus is the figure of Isaiah 9.

What do you expect Matthew to say next? If Jesus is “God with us,” the righteous Son of David, what should naturally follow? Yep, you guessed it. The very next verse, Matthew 4:17, records the first words spoken by Jesus in Matthew’s gospel.

Matthew 4:17 (ESV) “From that time Jesus began to preach, saying, “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.””

What is the kingdom of heaven? Is it a warm fuzzy feeling in the hearts of those whose lives are submitted to God? Is it a spiritual reign over a perverse world? Not according to Matthew. Isaiah does not only tell us about the king, but he describes the kingdom. He does that in chapter 9 and is more expansive in chapter 11. Matthew’s point is clear: Jesus is the king and he has come to bring the kingdom of righteousness and peace. Jesus would rule on David’s throne. This throne was a real (big) chair in Jerusalem, and sitting on it meant that you were in charge of the earthly affairs of the Israelite kingdom. The king would uplift the oppressed and strike down the wicked (Isa 11:4). Wolves would lie down with sheep, lions would become vegetarians, and the earth would be full of the knowledge of the Lord. That’s the “kingdom of heaven” that Jesus preached was “at hand.”

Now there are some kindly folk who think they ‘re getting Jesus out of a bind because quite obviously an earthly kingdom of worldwide peace was not established during Jesus’s ministry. They keep Jesus from being a liar by explaining that in fact Jesus was not talking about an earthly kingdom. Since no earthly kingdom appeared, what Jesus really meant was a kingdom in which he ruled in the hearts of those who loved him. All of that imagery, you understand, should be understood metaphorically. Ok, I ‘ll bite. Let’s play that game for a minute. The poor are now uplifted because Jesus is in their hearts; they ‘re so happy they don’t need a righteous judge in the law court. The wolf that lives with the lamb, that must be what’s happening in my heart, as bad thoughts and good thoughts live happily together. The child who plays with the snake, spiritually that must be fulfilled in that I can go into

(spiritually) dangerous places (like a bar) and yet not be hurt. The highway from Assyria that the Jews can return to Israel on, uh, hmm. You see, the only way that spiritualizing a passage like this works is by so generalizing it that details are completely irrelevant. This type of interpretation is not controlled by the text; it says what the interpreter wants it to say. You can understand it in a thousand different ways and no one could prove you wrong.

I believe in metaphors and symbolic language, but we must not create them where the author did not intend them. When Isaiah said that Assyria was going to smash Israel, the Israelites didn’t feel a cold and sharp feeling in their hearts (that’s the opposite of warm and fuzzy); they felt a hook through their lip as they were being dragged out of their land. When Isaiah said that after the Lord was finished with Assyria, he would destroy them (Isa 10:25-27), that’s exactly what happened (609 B.C.). Why is it that Isaiah’s prophecies of judgment were literally fulfilled, but his predictions of restoration are assumed to be 1) symbolic—thus a “spiritual reign” in our hearts, and 2) diverted—thus the descendants of the Assyrians, Egyptians, Babylonians and other Gentiles (but not the Jews) get the blessings as the church? Very simply, the reason why the “kingdom” is reinterpreted in such monstrous ways is to save Jesus from lying or being mistaken. The Jewish people today get this. They wonder, if Jesus was Immanuel, the Prince of Peace, where is this kingdom that he was supposed to bring? They are asking exactly the right question. In fact, the book of Matthew was largely written to answer just that question. That’s for another day. The point I must insist upon today is that we are being dishonest if we re-define Jesus’s (and Isaiah’s and Matthew’s) terms in order to save him. Jesus was the king of Isaiah 7-12, born to the prophesied virgin, born as the legal heir to the throne. The kingdom that he came to bring was the kingdom that Isaiah described. The reason that the kingdom was not established was not because it was really something altogether different.

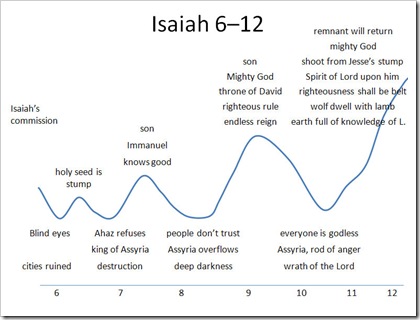

I close with two graphics that summarize most of what I’ve tried to cover thus far. If you prefer, you can download the PowerPoint and more extensive explanatory notes. In the first graphic, the point is that as Isaiah slides back and forth from judgment to hope, he is talking about a single judgment (deportation beginning with Assyria) and a single hope (an individual). The blue line goes back and forth between judgment (low) and ever-increasing and ever-defined hope (high). The chapter numbers are at the bottom.

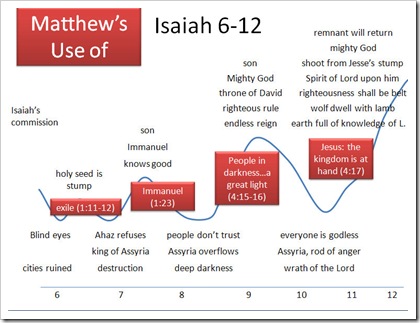

The point of the second graphic is to show how Matthew recognizes Isaiah’s point and argues that Jesus is the fulfillment of this prophesied individual.

The case is made stronger when you consider how the whole of Matthew uses the whole of Isaiah, and I ‘ll show you that later, but as this portion is somewhat defined and easy to see, I thought it good to give you a taste now.